One problem facing Guangdong is that although the entry threshold is lowered every year, migrant workers are not very willing to settle in local towns.

Source of this article Daily Economic News , author Yang Qifei.

On January 14, the two sessions of Guangdong Province were held, and Governor Ma Xingrui made a 2020 government work report. The two information disclosed therein caused a lot of discussions-

First, the GDP of Guangdong province is expected to reach more than 10.5 trillion yuan last year, an increase of about 6.3% year-on-year, which means that Guangdong has become the first “10 trillion” province;

Another thing is that Guangdong will liberalize restrictions on the settlement of cities other than Guangzhou and Shenzhen. In other words, the other 19 prefecture-level cities in Guangdong will lower their entry thresholds or even fully liberalize.

At the end of December last year, the two offices issued the “Opinions on Reforming the Mechanism and Mechanism for Promoting the Social Mobility of Labor and Talent”, which has been clearly deployed. The document mentions:

Removal of restrictions on settlement of cities with a permanent population of less than 3 million in urban areas; relaxation of settlement conditions for large cities with a permanent population of 3 to 5 million in urban areas.

According to the 2017 China City Statistical Yearbook data, only Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Dongguan are excluded from this column.

Mr. Lu Ming, Distinguished Professor of Antai College of Economics and Management, Shanghai Jiaotong University, and Executive Dean of China Development Research Institute pointed out to Uncle Cheng:

“Because the obstacles to the hukou system will hinder population inflows, in some areas with relatively developed economies in the coastal areas, labor shortages have occurred in recent years, and the relaxation of the hukou system is conducive to strengthening the population across the country Free movement and efficient use of labor can effectively alleviate labor shortages in coastal areas. “

The question is, will Guangdong’s liberalization policy solve the “urgent need”?

How serious is the “inverted population”

The issue of household registration has always been a “heart disease” in the Pearl River Delta cities.

Last year, Guangdong once again led the inflow of population, with an increase of 1.77 million permanent residents, becoming the only province in the country with more than one million in this indicator. Zhejiang is only 800,000 behind, less than half of Guangdong.

Where did these people go? If we do not consider the impact of intra-provincial migration, we will add up the changes in the permanent population of each city. The net increase of the permanent population in the 9 cities of the Pearl River Delta is 1.3045 million, accounting for more than 70% of the total increase in the province. Except for Guangzhou and Shenzhen, each of which divided more than 400,000, the remaining 7 cities added a total of more than 400,000.

These 7 cities will also be the cities most affected by this new policy.

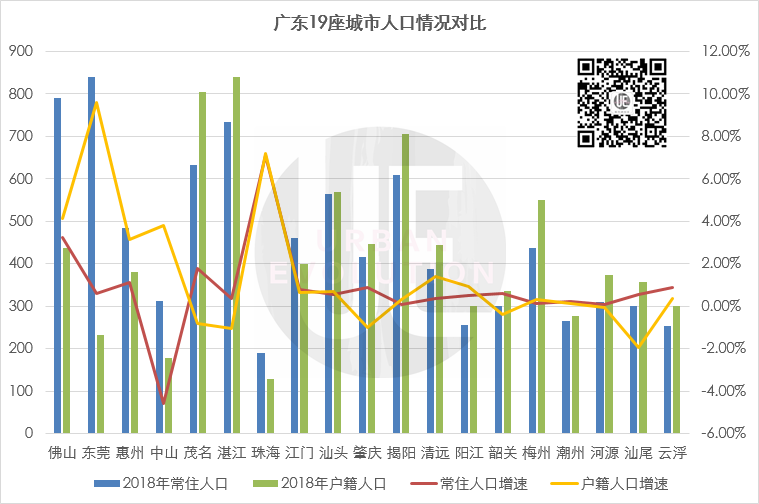

Since the data for 2019 have not been released, if the population of 19 prefecture-level cities in Guangdong except Guangshen is counted in 2018, the Pearl River Delta 7Except for Zhaoqing, the resident population in each city exceeds the registered population. Among them, Foshan’s resident population is nearly twice the household registration population, while Dongguan’s is more than three times, which is an obvious population inversion. This means that in Dongguan, there are more than 6 million permanent residents who have not obtained a household registration.

Data source: Statistical Bulletin of various places Collating and mapping: Urban evolution theory

What is this concept? We can follow suit earlier by saying that Shandong, a city with a permanent resident population of less than 3 million, can be set aside. Except for Jinan and Qingdao, which have a resident population of more than 3 million in the urban area, Shandong has 5 cities with more permanent residents than registered residents in 2018. But even Yantai, which has the biggest gap between the two indicators, only has less than 600,000 more people.

It is worth noting that these 6 million non-hukou populations belong to Dongguan’s “legacy of history.” In 2010, there were more than 3 million non-registered permanent residents in Dongguan. In the past ten years, the number has nearly doubled.

Why is the population upside down in Dongguan so serious?

As a major manufacturing city, Dongguan has a large number of migrant agricultural migrants. The “Dongguan New Urbanization Plan (2015 ~ 2020)”, which was issued in 2016, has proposed that by 2020, 900,000 agricultural migrants from outside areas will be transformed into citizens. And this is only part of Dongguan’s stock of migrant agricultural migrants.

In fact, the transfer of agricultural population is also considered to be the focus of liberalizing settlement restrictions at the national level.

In an earlier interview, Chen Yajun, director of the Development Strategy and Planning Department of the National Development and Reform Commission, pointed out: “The civicization of agricultural transfer population is the primary task and core task of new urbanization. We say that new urbanization based on people must first be The solution is the issue of the civicization of the agricultural migration population. “

Continuous policies and poor results

The PRD cities were at the forefront in promoting the civicization of the agricultural migration population and resolving the population inversion problem.

As early as 2010, Guangdong led the nation in implementing the points-to-home policy to lower the entry threshold for migrant workers. Later, the policy was rolled out nationwide and written into official documents at the national level.

In 2014, the National Government Work Report stated that “for a period in the future, we will focus on solving the existing ‘three 100 million people’ problem,” including “promoting the transfer of about 100 million agricultural migrants to cities and towns.” In the same year, Guangdong Province held a conference on urbanization.The urbanization rate of the resident population should be increased to 73%, the urbanization rate of the registered population should reach 56%, and no less than 6 million of the province’s and 7 million foreign provinces’ agricultural transferred population and other permanent residents should settle in cities and towns.

A year later, Guangdong immediately issued the “Implementation Opinions on Further Promoting the Reform of the Household Registration System,” which once again adjusted the household registration policies in many cities, including Zhuhai, Foshan, Dongguan, Zhongshan, and other Pearl River Delta cities.

But compared to the goals that have been set, Guangdong’s progress is not satisfactory.

Since the recent non-farm household population data is not disclosed in the statistical bulletin, we may wish to use the urbanization rate of the permanent population for calculation. The statistical bulletin shows that in 2014, the urbanization rate of the resident population in Guangdong at the end of the year was 68%. Four years later, the indicator rose to 70.70%, an increase of only 2.7 percentage points. If this rate is to be met, whether Guangdong can reach its original target of 73% this year still needs to be marked with a “question mark”.

The registered population increase is more optimistic. In the three years from 2014 to 2017, Guangdong’s household registration population increased by about 4.3 million. But how many of them belong to the agricultural migration population is also unknown.

Specifically, at the city level, the situation of “more policies and less effects” is more obvious.

Take Dongguan as an example. Since the introduction of the point system in 2010, although the threshold has been continuously lowered through three amendments to the policy, by August 2015, of the population of more than 6 million people at that time, only 11,554 applicants who meet the qualifications for entering the households have gone through the registration procedures (6010 people with points-based talents and 5,544 people with conditional admissions), and the number of households registered each year has not increased significantly.

Peng Hui, then a member of the Guangdong Provincial Public Security Department’s party committee and deputy director, once pointed out that one of the problems facing Guangdong is that although the entry threshold is lowered every year, migrant workers are not very willing to settle in local towns.

Can it still be attractive if you let go?

In this case, how effective is the threshold for resettlement from “lower” to “lower”?

Some experts have speculated that the possible effect would be “the ones who can settle down can still be settled, and the ones who failed to settle down will probably not settle down.”

From the perspective of outsiders, there is a lack of motivation to settle down. There are many reasons.

On the bright side, some of the public service issues that had previously been resolved through settlement can already be solved in other ways. For example, in Dongguan, the “point-to-school policy” has, to a certain extent, solved the education of migrant children.

On the other hand, the huge differences in urban and rural life have greatly increased the economic and psychological costs of migrant workers. For example, Zhang Yan, an associate professor at the Peking University Guanghua School of Management, wrote that under the higher housing and education expenditures, the monthly income of migrant workers is almost in vain.

A more general view is that the effectiveness of policies ultimately depends on the basics.Whether this public service can be equalized.

According to Lu Ming’s analysis, even though Dongguan has made several reforms to the settlement system, taking the point settlement system as an example, the point standard is still high.

“Because in the economically developed areas of big cities, local hukou status and corresponding public services are not available, there is a huge concern for immigrants, so of course they are unwilling to give up their hukou.” < / p>

Conversely, for cities, deregistration of household registration is not as simple as a single policy. It is more important to pay attention to the matching of public services, which in turn requires the government to spend more financial resources to support it.

According to previous media calculations, according to Guangdong ’s 7 years of promoting 13 million people to settle down, the per capita cost of Guangdong ’s agricultural migration population includes a one-time cost of 134,100 yuan and an annual public service cost of 6,581 yuan. Guangdong ’s one-time cost will be as high as 7 years. 1.7 trillion (131.4 million × 13 million), the annual cost of new public services is up to 12.2 billion (13 million / 70,000 × 6581 yuan).

Even if you consider the effect of scale, this is still a significant cost.

In the view of Lin Jiang, deputy director of the Hong Kong, Macao and Pearl River Delta Research Center at Sun Yat-sen University, cities should take the lead in taking a stance to fill some public service vacancies and attract more people to settle down; the settled population will also bring more to the city Economic benefits, improve finance, and form a virtuous circle. But the problem is that many cities now face downward economic pressure and financial pressure, and it is difficult to press the “start button”.

Earlier, Cai Yan, deputy dean of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the uncle Cheng that the reform of the household registration system is still unsatisfactory. The more fundamental reason is that the local government has insufficient incentives, and there is an “asymmetry” in reform revenue and expenditure costs. He therefore suggested that this reform dividend should be paid by the central government as a “public good”.