Last week, the number of friends who urgently invited me to analyze the international trade crisis doubled. Ignoring the well-known background situation, the questions are concentrated in the following areas:

1) Should foreign words and deeds be responded strongly or quietly?

2) Looking to the future, if there is a serious lack of mutual trust, how to maintain international trade cooperation?

3) The essence of trade is mutual benefit. Mutual harm may be the exception. Will the struggle end soon?

I am a layman in international trade. However, it is still possible to identify the “prisoner’s dilemma” presented by the current international trade. For how to get out of the “prisoner’s dilemma”, game theory has been researched for more than 30 years. In many cases, a classic theory that summarizes the essence of a phenomenon has extremely high practical value. In short, even if you are in a game of severe lack of mutual trust, if the strategy is right, a cooperative relationship is still possible. It is also possible if the strategy is improper and the two sides fall into a long-term mutual harm relationship and cannot extricate themselves.

World War I, the tacit cooperation between rival soldiers

World War I exposed a series of misjudgments by political decision-makers. First, the oppositional alliance represented by Britain and Germany misjudged the symbolic significance of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Duke of Austria. Second, the two sides believed that the symbolic confrontation of force could end within a few weeks. As a result, World War I lasted for 4 years, with 42 million casualties.

There is another phenomenon unexpected to the decision makers, which is the peaceful cooperation in the interaction between the enemy and ourselves. In the 500-mile trench tunnel extending from France to Belgium, soldiers from both sides deduce a rare phenomenon in the history of military warfare: In addition to intermittent raids, soldiers can live normally within the rifle range of both sides without fear of the opponent’s sniper shooting. kill.

The historian Tony Ashworth is very curious about this phenomenon. By reading the family books and diaries of a large number of frontline soldiers, he recorded the special cooperative behavior of the two opponents in the war with the book “Trench War 1914-1918” (Trench War 1914-1918).

Since August 1914, the war has been bloody and cruel, and the two sides have intervened in a life-and-death zero-sum game.play. Due to accidental factors, in some positions, the time when the two sides buried their pots and stoves were just the same. A strange silence appeared on the battlefield. The tacit understanding formed by accident extends from a truce to eat to getting up and showing respect. From 8 to 9 in the morning, the British and German soldiers maintained a state of non-aggression, allowing everyone to deal with private affairs. Later, both parties invariably gave up the attack on the food supply line, and wanted to eat themselves, but also let the other party have food to eat.

The tacit understanding of mutual restraint spreads from one tunnel to another. On Christmas 1914, drunken soldiers could even stroll into the trenches without worrying about being shot. Of course there will be accidents, this is war after all. When one party launches a surprise attack, the other party immediately counterattacks, one life worth one life. During the truce, German snipers would deliberately aim at the houses above the British trenches and shoot continuously until they made a beautiful round hole. Soldiers on both sides used similar methods to demonstrate their ability and willingness to retaliate. A report pays a report, I live and let you live, and at the same time, I will pay for it.

According to the logic of war, the two opposing parties form a typical prisoner’s dilemma. Mutual betrayal should be the norm. However, the soldiers in the trench war showed another aspect: betrayal in a raid, cooperate in a truce, seek a way of survival by themselves, and let the other party have a way to survive. Peaceful cooperation between the tunnel soldiers, of course, caused dissatisfaction with the headquarters. The commander always has a way to continue the war. It is another story. However, in the protracted trench war, how did the enemy soldiers reach a tacit understanding of cooperation? In the next 100 years, it has been a hot topic for scholars of game theory.

Beyond the Prisoner’s Dilemma

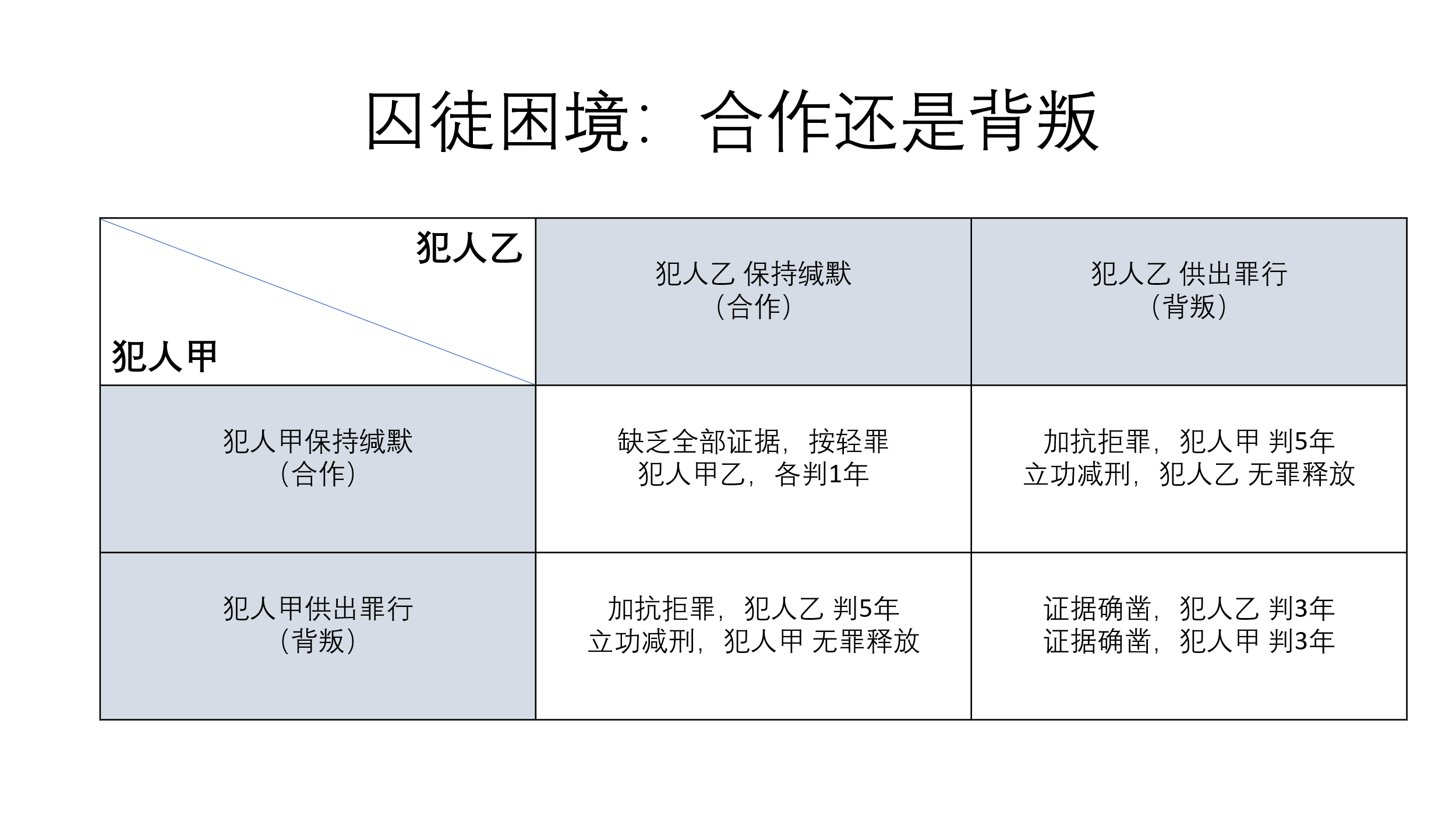

In 1950, Rand Corp began to study the Cold War game between the United States and the Soviet Union. The mathematician Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher (Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher) deduced the famous “Prisoner’s Dilemma” (see picture below). In a hypothetical game between prisoner and prisoner, if the two collude in advance and both remain silent, then each will be sentenced to 1 year. If one of them betrays and the other still refuses to confess, then the criminal who betrayed can be exempted from punishment, and the criminal who resisted the confession will be sentenced to 5 years. If both of them betrayed the prior collusion, they were each sentenced to 3 years in prison. After detention, because the two prisoners could not communicate, the first choice of reason was generally more inclined to betrayal. In the absence of information and reliable commitments, it is an advantageous option for maximizing personal interests.  “Prisoner’s Dilemma” has influenced a generation of international relations scholars. In the process of competition between the two superpowers of the Soviet Union and the United States, betrayal and confrontation became the first choice and the first choice of the great power game. When Allison ( When Graham Allison talked about the Thucydides’ trap of great power conflict, the logic behind it is also the same.

“Prisoner’s Dilemma” has influenced a generation of international relations scholars. In the process of competition between the two superpowers of the Soviet Union and the United States, betrayal and confrontation became the first choice and the first choice of the great power game. When Allison ( When Graham Allison talked about the Thucydides’ trap of great power conflict, the logic behind it is also the same.

Is it impossible to cooperate without mutual trust? How? Can the choice under the prisoner’s dilemma be reversed? During World War I, the spontaneous cooperation between the enemy and our soldiers was only a flash in the pan, or could it be maintained for a long time?

With the above questions, University of Michigan The political scientist Robert Axelrod has modified an important but overlooked premise of the prisoner’s dilemma: Imagine that the two sides of the hostile enter into a cyclical, continuous process of interaction, and what choice (cooperation or Betrayal) will win? This winning choice should be stable and should conform to the long-term interests of the chooser.

To understand the laws behind the long-term game, Axel Rhodes designed a computer game. The game imitates the prisoner’s dilemma, but does not set an end condition. In other words, the game participants do not know whether the next game is final. In 1980, Axel Rhodes studied game theory and related social sciences. Of scholars sent out hero posts, inviting them to volunteer to participate in the prisoner’s dilemma game.

The participants in the first round of the tournament are game theory enthusiasts or experts. You come and I, In the 14 rounds of the game, a professor from the University of Toronto got the first score. He used a very simple strategy: Tit for Tat, that is, you are good to me and I repay with kindness; you are evil to me , I will retaliate and fight back; so, the cycle does not change.

The second round of the tournament has 62 games. Participants from 5 countries are already familiar with the previous round. The result of the game, especially the winning strategy. Participants try 15 different combinations of cooperation or betrayal strategies, including the “deception strategy” (two consecutive betrayals when appearing on the stage) and the “deception strategy” (cooperate in the opening and then betray consecutively) , “Robber strategy” (betrayed all the time, never cooperate), “Take advantage of the opportunity strategy” (cooperate once, betrayed twice, and then apologize for mercy). Surprisingly, the top rankings are all using “a newspaper” The strategy of “pay back”.

The initial research problem of Akselrod is: starting from self-interest, without authoritative intervention, lack of trusteight”>